Against Efficiency

A celebration of the inefficient, the transitory, the dilatory, the slow rhythm of human impulse, desire, and imagination

There’s a lot of efficiency in my house. My dishwasher is energy efficient. My washer and dryer have an Energy Star rating. The fridge probably does, too, but it came with the house, so I’m not sure. When we replaced the HVAC, we purchased the most efficient heat pump we could afford, a splurge that got us off natural gas. My home is loaded with efficient machines, efficient systems, and efficient designs.

I am not one of them.

I’ve been known to take a nap at 9:30 in the morning because I can’t focus on my work. I’ll try to write, to make notes for the novel or an essay or some other project, and it’ll be like trudging through molasses, so I’ll take a thirty minute nap even though I’ve really only been up for about two and a half hours anyway. I take a nap probably every day because I’m useless unless I can close my eyes for half an hour after lunch.

When I revise, I fully retype my manuscripts, start to finish. It took me six months to copy edit my dissertation after I finished my PhD. (Which is also when I discovered just how egregious the typos in the manuscript deposited with the university.) In truth, it probably took me longer when you consider how easily distracted I can get by new, flashier projects.

I’ve tried to find faster ways to grade, but anything I find makes it feel like I’m short-changing my students, so I fall back on my old methods. I’m still faster than I used to be, but never as fast as I (or my students, probably) would like. Practice makes it easier, but probably never more efficient. To say nothing of lesson planning.

I’m in the throes of an agent hunt, which means that I’m reading deep into agents’ client lists. Though, to be fair, this might be more anxiety and procrastination (and are those really all that different?) than it is inefficiency.

I savor growing vegetables in my garden, waiting until the peppers are the sweeter, more vibrant red than the pale green you can get in the grocery store. I like to cut vegetables slowly, prepare ingredients slowly, cook slowly (except when it needs to be cooked quickly over a high flame, of course). I like to smoke a brisket from time-to-time, which means waking up at 4 or 5 in the morning and, with a cup of coffee, starting a fire that I’m going to monitor all day so I can have dinner on the table by like… what? 7… 8pm? Whenever we get past “the stall,” I guess. I like taking back roads on long roadtrips (though I don’t do this nearly as often as I would like). I like reading three or four books at a time and getting them confused with each other. I like flipping through the stacks at a record store, finding eight things to buy, purchasing none of them, and leaving an hour later.

I’m not a patient person, not even slightly, but I’m hardly efficient. I tried productivity hacking for a bit in my twenties. I’ve read Cal Newport’s Deep Work, told myself that I need to “eat a frog first thing,” bought a timer so I could do modified pomodoros. I do my best, most interesting work in the mornings and then in the late afternoons, so I’ve tried to work my schedule around that pattern as best as possible, I suppose. Though, this is less about productivity than it is engagement and creative energy. Anyway, the timer broke, and I’ve never actually eaten a frog to the best of my knowledge.

I’ve also never understood what all that energy expended toward productivity was actually buying me anyway. The “Protestant work ethic” gave way to productivity hacking and created a market of self-help gurus, bullet journal content creators and bloggers selling journals and pens and breathing techniques and shoddily designed digital timers in the process. Hard work as a moral virtue transformed into productive work as a step toward achievement. I’m not outrageously successful by any real metric, so I guess take whatever I say with as many grains of salt as you’d like.

There’s value in those productivity practices, I’m sure, so I’m not trying to shame anyone who finds value in them. Certainly set times to remind yourself to take breaks—I’d do it too if that timer hadn’t broken—but efficiency seems to be the one metric we’ll prioritize over nearly everything else: from automation to the assembly line to auto-complete texts, email reply suggestions, dinners cooked in under thirty (under ten!) minutes. If it can be done, then it can be done quickly.

Work hard for God’s favor. Work smarter for your boss’s.

But when we joke about how we can’t schedule an evening out with friends for the next six months, when relationship coaches seriously suggest we schedule time for sex with our partners, I’m wondering if we’ve missed the point entirely.

Now, the DOGE-boys are turning AI loose on the public good, searching out ways to make the NEA, NEH, NIH, FHFA, NPS, BLM more efficient. So what do we mean by efficiency anyway? Improved mechanical and electrical systems? Sometimes. Improved bureaucratic systems? Seems so. But how? What about improved daily routines? Diets? Gym workouts? Some people are out in public media talking about inefficient expenditures a lot these days, which seems to be a handwaving cliché encompassing everything from the salaries of civil servants to Medicaid. It’s unlikely the teenagers and GOP politicians breaking the government will pull the US back into the black in any event. Time is money, I guess, no matter how you spend it.

Setting aside the sleight of hand that defines the current political obsession with efficiency, which is really just a rhetorical maneuver to elide the real aims and goals of the current administration, it’s probably high time to push back against our contemporary faith in efficiency.

There’s nothing wrong with getting things accomplished, but that doesn’t have to mean efficient. I would rather struggle to find the word I’m looking for than have Google help me find it. And friends, I’m in my forties, so I spend a lot of my time trying to remember the word that was just on the tip of my tongue a minute ago. It’s embarrassing when I lose the thread in front of my students, or, frustrated that I can’t remember “French press,” ask my wife to hand me the “coffee plunger,” but that’s just part of being human. We’re fallible and failing organisms gradually decaying, and not a lot is going to change that.

Instead of worrying about how productive I am—and frankly, what is less productive than writing an essay about productivity on Substack?—I want to celebrate inefficiency. I want to revel in the fleshy fact of my failures of logic, of creative impulse, of achievement.

The word “efficiency” makes a remarkable semantic shift across the history of the English language. The earliest recorded use of the word in the OED dates from 1593, defined as the “fact of being an operative agent or efficient cause.” The earliest entry in the OED is from Richard Hooker’s Of the lawes of ecclesiastical politie: “The manner of this diuine efficiencie being farre aboue vs.” The next entry is Thomas Spencer from 1698: “God is sayd to be the Efficient Cause of man: the office of this efficiency, is placed in ioyning the forme vnto the matter.” 1 Here in this earliest definition, now only used in philosophical discourse, the word refers to the agent that makes something operate. In both of these entries, we see God as the agent, the moving force that sets the world into motion by joining form into the matter. It means a motivating, activating force that sets life in motion.

A later definition is more closely aligned with how we define “effectiveness” today. It’s the “fitness or power to accomplish, or success in accomplishing, the purpose intended.” Entries in the OED here relate to the effectiveness of the law, the British navy, and religious practice. This is no longer about causes but about effective use of power. The 1863 entry from Henry Fawcett shows us something of the shift becoming apparent: “Nothing more powerfully promotes the efficiency of labour than an abundance of fertile land.” 2 Here we’re still defining efficiency by its power to produce intended outcomes, but through its coupling with labor (and with capital) we’re witnessing a shift from the mere fact of being the agent that puts things into motion to the power in producing outcomes.

Notice the change and consider what it means. What’s happened between the late sixteenth century and the mid-nineteenth? In 1827, the OED records the first usage in relation to mechanics—“the total energy expended by a machine.” 3 These are largely mechanical calculations used to quantify output (and thus the value) of a system. There are subtle shifts in usage here—a transition from “the work done by a force operating in a machine or engine” to “the ratio of useful work performed to the total energy expended or heat taken in”—but they shouldn’t necessarily concern us. 4 What we should pay attention to is the shift from agency to power and a calculable interchange between energy and production—the productivity of a machine.

It’s not until the early twentieth century that the term takes on a meaning for economics. The 1953 entry from Graham Hutton easily highlights the meaning of this shift: “Productivity is the efficiency…of production.” 5

Google Ngram shows us the explosiveness of this term. We see a rise in its usage in the middle of the nineteenth century to its heights in the early part of the twentieth century. From there, it balances though hardly tapers off.

Our modern uses of the term seem to evolve from two places, then. First, the effectiveness of mechanical production based on the relationship between energy expended and productivity gained. Second, this mechanical definition generalized to incorporate economic and non-mechanical inputs and outputs in a system.

It seems a rather obvious point that “efficiency” undergoes this semantic shift alongside the industrial revolution. The first automated machines that begin to upset the British textile industry were invented in the middle of the eighteenth century. The mechanical loom a little later. 6 The development of these machines and their employment in the textile factories of northern England would go on to set off the Luddite Rebellion in the 1810s. James Watt’s steam engine was finalized in 1790, which replaced the water wheel and permitted factory owners a greater flexibility in selecting the location for their operations, which in turn gives them greater control over the laborers in those factories.

All of this is to say that when we say something is efficient, we need to ask who that efficiency benefits. The word, in its modern orientation, is coupled with bosses, with ledgers and bankbooks, with earnings, with capital. It is not concerned with, let’s say, you and me.

The machines that break human agency in the name of efficiency aren’t simply machines, then. They are devices that, yoked to the idea that progress only moves in one direction, “disrupt” whole systems—systems that are built on communities and ecosystems. These systems evolve so that relationships between people are reframed in favor of commercial efficiency with or without the machine. Now we’re watching the specter of automation rise again to make our efficient systems even more efficient. It’s going to crawl through data to find inefficiency, we’re told. It’s going to make our jobs easier or nonexistent, depending. It’s going to replace our friends, apparently.

All of these proposals are narratives, of course. They depend on the “fictions” (using Walter Lippmann’s sense of the term) through which we negotiate our understanding of the world. It’s common to hear that tech is neutral, but it really isn’t. Without our systems of power, derived from our understanding of the way the world is shaped, our tech would simply look different. Our narratives shape both the tools and their application. Why is it necessary, for instance, for AI to attempt to replicate human writing? Why do I need Google to crawl through my emails and my docs to auto-complete emails that I could just as easily write myself? If AI is the next great search engine, why are its outputs more concerned with sounding correct than being correct?

Because the conditions of our existence are shaped by the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the world—something neither good nor bad, necessarily—when we tell stories about how productivity and efficiency created progress, that story has tremendous power. If we begin to tell the story differently, that will have power, too.

So I want to celebrate inefficiency. I want to celebrate spending all day working on something and then realizing you were doing it wrong. I want to celebrate wondering about something and never knowing the answer. I want to celebrate walking to the library. I want to celebrate having weird conversations with strangers. I want to celebrate being too tired to work, being too excited to focus, being too sad to create. I want to celebrate reading books on paper, finding those books at a book store, and if they don’t have what we’re looking for, having to wait until it comes back in stock. I want to celebrate long meals and late mornings.

I want to celebrate not working, being broken, being heartbroken, being rendered utterly overwhelmed in the face of human extravagance and sorrow. I want to celebrate staring at the night sky and not being able to look away from the infinity of it all. And I want to celebrate being angry when a train of Starlink satellites race through all of that glory.

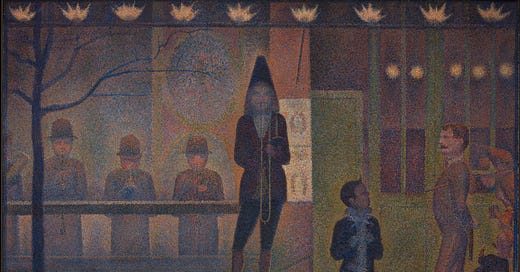

I want to celebrate art because there is nothing efficient about art. Art is thinking in public. It’s speaking in public. Neither thinking nor expressing are efficient most of the time.

The opposite of the efficient is the human. Humans are inefficient all the way through. That’s why we want all of these tools to keep the systems going. We’re inconsistent, contradictory, irrational. God, our emotions get in the way. God, we get in bad moods and react to something in a way that we will most certainly regret later. God, when we love something, we turn a blind eye to its faults. And God, sometimes we get hungry and have to eat, and sometimes we’re not hungry and go ahead and eat anyway.

I don’t want to be efficient. I want to be human. I think that will always matter more than my ability to reply to all of my emails within a single business day.

And when I’m wrong, when I later disagree with something I wrote here (or worse, got something wrong!), I guess I’ll embrace that, too. I’m not an efficient creature.

Oxford English Dictionary, “efficiency (n.), sense 1.a,” March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9043895170.

Oxford English Dictionary, “efficiency (n.), sense 2.a,” March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1071678032.

Oxford English Dictionary, “efficiency (n.), sense 3.a,” March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4753051902.

Oxford English Dictionary, “efficiency (n.), sense 3.b,” March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5627316442.

Oxford English Dictionary, “'economic efficiency' in efficiency (n.), sense 2.c,” March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/8902356794.

Merchant, Brian. Blood in the Machine: The Origin of the Rebellion Against Big Tech, pp. 10-11.